Democrats’ best chance at clawing back any power in Washington in the midterms runs through the House after Republicans claimed a trifecta in November.

But several redistricting cases in courts across the country could alter the battlefield before the first votes are even counted.

Mid-cycle redistricting has become the norm in recent years, as perpetual lawsuits concerning partisan and racial gerrymandering have drastically altered competitive districts across the country.

Last cycle, changes to district lines in North Carolina could have been an influential factor in Republicans holding their majority. A U.S. Supreme Court decision permitted an unchecked partisan redistricting process, and the Republican-dominated General Assembly configured the lines to wipe out three Democratic-held seats.

Republicans, however, reject the premise that North Carolina led to their majority, pointing to Democratic-led gerrymandering in Illinois, New Mexico, and New York.

“House Republicans won the popular vote by the largest margin since 1928,” National Republican Congressional Committee Communications Director Will Kiley told National Journal. “It is ridiculous to claim we only hold the majority due to North Carolina when the facts clearly paint a different picture.”

Changes to congressional maps are expected once again, and an early prognosis found Republicans may stand to gain from current battles in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, and Ohio as they prepare to defend their three-seat majority.

“The last time the U.S. Congress ran on a map back-to-back was the 2012 to 2014 cycle,” National Democratic Redistricting Committee President John Bisognano told National Journal. “That is not going to happen this year.”

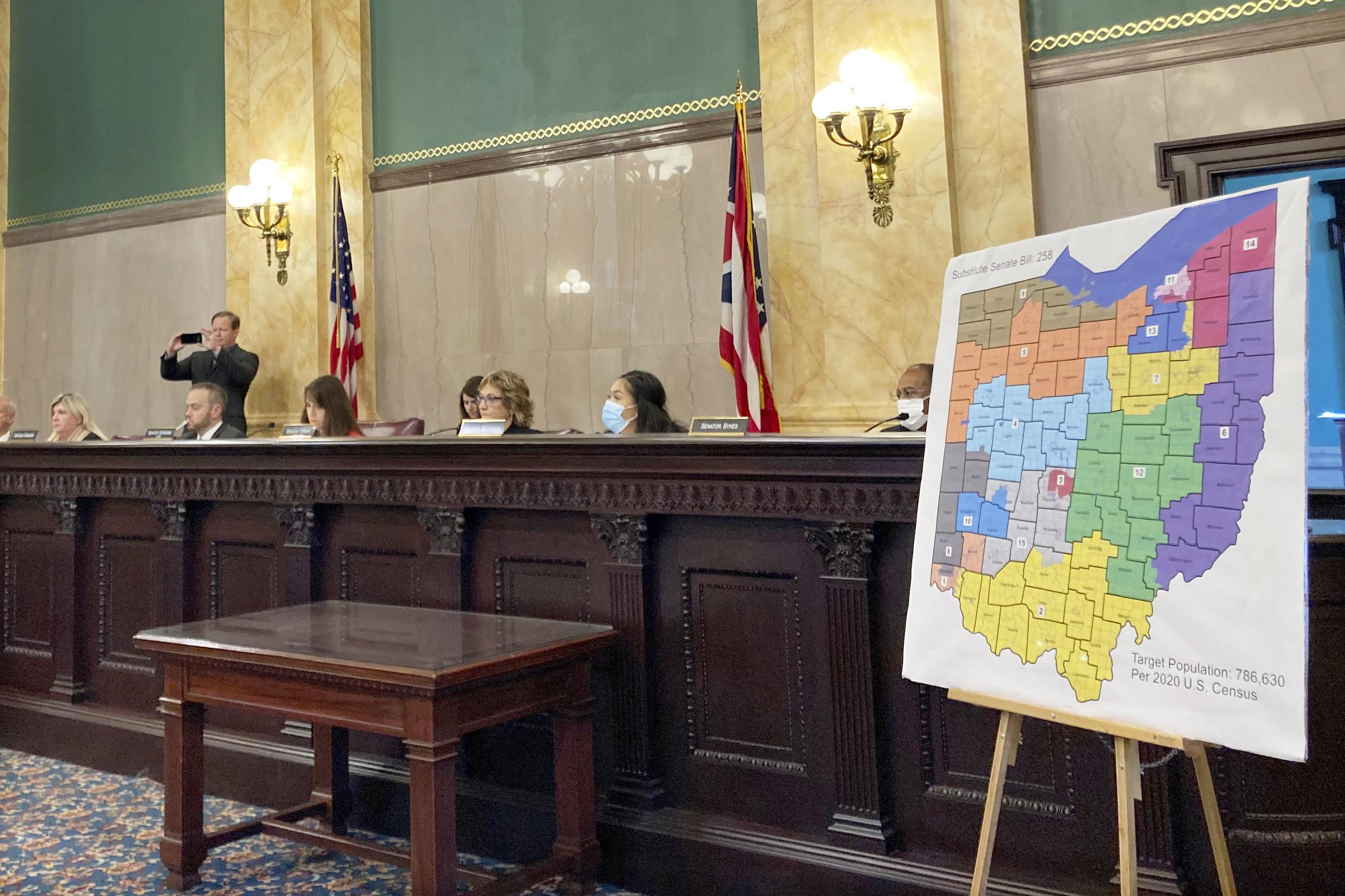

The most poignant example is Ohio, where the bipartisan redistricting commission must redraw the map. The Buckeye State’s convoluted map-drawing process requires maps to be used for four years if they are approved along party lines, and the 2022 map—which saw multiple iterations and legal challenges—expires ahead of the election.

Republican campaign operatives hope the commission, led by the GOP, will craft a map in their favor and threaten up to two Democratic-held seats.

“We kind of have a watered-down map from what we really hoped we were going to get the first time around,” said Adam Kincaid, president of the National Republican Redistricting Trust. That map, which Democrats challenged and the state Supreme Court ruled invalid, all but ensured 10 Republican seats and gave them an advantage in two of the three competitive seats.

“Hopefully the good folks in Ohio can get things right this time,” Kincaid said.

A map similar to the 2021 version would further endanger Democratic Reps. Emilia Sykes and Marcy Kaptur. Former Vice President Kamala Harris narrowly carried Sykes’s Akron-based seat, while President Trump expanded his margin in Kaptur’s Toledo seat.

The South, which had major redistricting developments during the 2024 cycle, could again be a source of angst for Democrats and Republicans alike. Alabama and Louisiana each gained a Black-majority seat after legal challenges based on the Voting Rights Act when the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act in both cases. Democrats won both Black-majority seats in November.

But there’s reason for Democrats to be concerned about the longevity of those lines. In Allen v. Milligan, the case that created a second Black-majority seat in Alabama, Associate Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh wrote in part that “the authority to conduct race-based redistricting cannot extend indefinitely into the future,” but he would “not consider it at this time.” Kavanaugh’s suggestion that he could be open to dismantling Section 2 in future legal cases worries some Democrats.

“We should always be concerned about the possibility of new and greater challenges to the Voting Rights Act and vigilant about defending the VRA,” attorney Abha Khanna said. Khanna heads the redistricting program at Elias Law Group, a major law firm for the Democratic Party.

But, she said, “the precedent has been clear for a very long time, and we've not been given any reason to think that it's time to just flip the table over and upend all of that precedent.”

The Supreme Court is expected to hear arguments for the Louisiana case during its current term after the high court stayed a challenge to the revised map. The trial for the court-drawn map in Alabama begins in February.

Plaintiffs—and Republicans—in Louisiana insist the remedial map is a racial gerrymander, as the district court ruled last year before the Supreme Court stepped in to stay the case. The Supreme Court’s ruling this term could have major implications for future race-based redistricting.

The National Republican Redistricting Trust’s Kincaid said he hopes the ruling will “provide some overall clarity on the tension that exists” between the Voting Rights Act—which protects minority voting power—and the 14th Amendment, which Louisiana's district court ruled the map violated under the equal protection clause.

Arguments were also heard last week in Georgia, where last year Republicans preserved their stronghold while satisfying the requirements of the Voting Rights Act. If the state were to win its challenge, the ruling could pave the way for the Legislature to expand the GOP-dominated congressional map. Georgia currently has nine Republicans and five Democrats in the lower chamber.

Florida awaits a decision from its Supreme Court after voting-rights-group plaintiffs won a racial-gerrymander case at district court. The case concerns a Black-majority district in North Florida that stretched from Tallahassee to Jacksonville. Republicans wiped out the seat during the apportionment process in 2021.

But the state won its case at the appellate level, and both parties now await a decision from the state Supreme Court. Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis appointed the majority of the court’s justices, and its decision will likely determine which party holds that seat.

Democrats hope redistricting cases might break their way in a handful of states. Utah’s Supreme Court reversed a district court ruling that dismissed a challenge to the state’s redistricting process. A challenge from voting-rights groups said the Legislature ignored a ballot initiative that established an independent redistricting commission.

Dan Vicuña of Common Cause, a nonpartisan organization that advocates for fair maps, told National Journal that the case now heads to trial.

“The Legislature attempted to really gut that [commission], and then passed a very partisan map,” he said. “So the state Supreme Court shut down the Legislature's efforts on that, and now it's got to actually go to trial.”

If the effort is successful, changes around the Salt Lake City area could create a potentially competitive seat ahead of the 2026 midterms.

Beltway Democrats also hope potential lawsuits and a state Supreme Court election that will determine the balance of the court in Wisconsin could reignite a redistricting discussion. The state’s high court declined to take up a challenge to the case last year.

Bisognano said he expects changes to maps across the country despite the fact that last cycle’s map was “more competitive than probably any map we've seen in the past at least 50 years.”

A successful redistricting cycle, he said, would maintain that competitive ethos.

“Giving all parties access and ability to compete on their ideas, as opposed to maps that draw one party into and/or out of power, is going to be the way that we try and measure success,” he said.