Advocates say they are worried that Medicaid cuts will lead to a loss of services and providers that help keep Americans with disabilities out of institutions and in their homes.

Medicaid covers more than one in three Americans with disabilities, including services in schools and home- and community-based services. But cutting federal funding for the program may force a slashing in benefits or payment rates for providers, effectively cutting off access to needed services, disability advocates warn.

“Medicaid is everything,” said Maria Town, president and CEO of the American Association of People with Disabilities. “Medicaid helps to facilitate health care for kids with disabilities and students with disabilities in school. It helps to facilitate education.”

Town added that Medicaid is “essential to ensuring the civil rights of people with disabilities” because it supports individuals living in the community rather than in nursing homes or other institutions.

While Republicans are still negotiating topline numbers, the House-passed budget resolution has Democrats and advocates worried about the future of the Medicaid program because it calls for the House Energy and Commerce Committee to find $880 billion in savings.

Rep. Brett Guthrie, the Kentucky Republican who chairs the committee, told National Journal Tuesday that plans to potentially reform Medicaid are still in flux as lawmakers wait on what could be the Senate's final number for their budget. Guthrie said the committee could meet the $880 billion target and the savings wouldn’t entirely be generated from Medicaid, although a recent Congressional Budget Office analysis indicated that a significant portion of the cuts would have to come from the program.

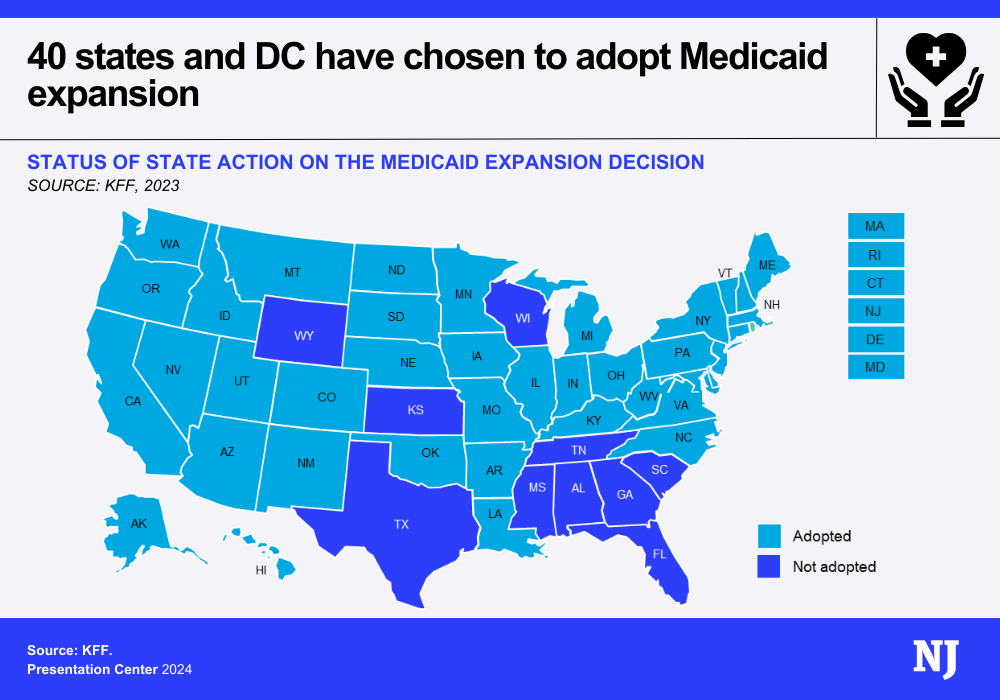

He expressed concern about the growth in Medicaid spending and suggested looking at the population that is covered under Medicaid expansion. The Affordable Care Act allowed states to expand coverage for individuals making up to 138 percent of the poverty level, and the federal government covers 90 percent of their health care costs, while states pick up the other 10 percent.

Guthrie noted the disparity in the share the federal government pays for the expansion population versus traditional Medicaid beneficiaries. “It incentivizes states to move people into the other population. If we start dealing with that, we can hit our number,” he said.

In Guthrie’s home state, the federal government pays for 71.5 percent of health costs in the traditional Medicaid population. Kentucky also implemented Medicaid expansion in January 2024.

He said lowering the share the federal government covers from 90 percent to the normal Federal Medical Assistance Percentage “might be too much” for some people. But he said creating per-capita caps specifically for the expansion population, which means paying a set allotment per enrollee, is on the table.

When asked about concerns from disability advocates, Guthrie said the committee can generate $880 billion without making changes for people with disabilities on traditional Medicaid.

But slashing dollars could force states to pare back optional benefits for Americans with disabilities and decrease worker reimbursements. John Poulos, a policy analyst at the Autistic Self Advocacy Network, said the Republicans’ goal is to shift more Medicaid costs to the states. He said this could reduce provider payment rates, leading to service closures among rural providers.

Poulos also said home- and community-based services, which are optional services that state Medicaid programs can cover and are “relied on heavily by people with disabilities,” could be vulnerable.

“States will have to cut optional services like home- and community-based services first to make up any budget hole,” he said. “The loss of home- and community-based services means more hospitalizations, family caregivers leaving the workforce to provide care, or people going without care entirely, which can mean, and will mean death,” he said.

Several advocates raised concerns specifically about home- and community-based care. Medicaid is the largest payer for these services, spending $129.4 billion in 2022 benefiting 7.8 million people, according to an analysis from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Services can include personal care, case management, and adult day care.

“For a lot of our population, our constituents, Medicaid is the only payer for home- and community-based services,” said Kim Musheno, senior director of Medicaid policy at The Arc, which advocates for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Musheno said these services can help people with disabilities work through transportation and employment support.

Kendra Davenport, president and CEO of Easterseals, which provides these and other services to individuals with disabilities, said providing such services keeps people in their homes and out of institutions.

Davenport said Medicaid cuts will result in job loss on multiple levels. “The cascading effects of unemployment due to Medicaid cuts could be devastating,” she said. “For every home health care worker that’s laid off due to Medicaid cuts, there’s a ripple effect across the economy. When a home health care worker loses their job, a family member has to step in and likely leave the workforce.”

Americans with disabilities could also be at risk of losing coverage if states reconsider eligibility. The Medicaid program is required to cover individuals receiving Supplemental Security Income, which provides a monthly income to individuals who are unable to work due to a disability. But two-thirds of Medicaid enrollees with disabilities do not receive SSI, according to a KFF analysis. They can enroll through other pathways, including the Medicaid expansion, and can be subject to work requirements if those are implemented, the report says.

Alice Burns, associate director of KFF’s Program on Medicaid and the Uninsured, said many Medicaid enrollees with disabilities could find their coverage at risk under work requirements. “In many cases, we hear that Medicaid work requirements are framed as applying only to able-bodied adults, which implies that people with disabilities will not be affected, but that’s really not the case,” she said.

Burns also noted the tight limitations on qualifying for SSI: An individual or a couple must have little to no income. Resource limits are set at $2,000 for individuals and $3,000 for a couple.

She said people with disabilities could have incomes that qualify them for Medicaid but not SSI.

States provide other optional pathways for individuals with disabilities who make too much for SSI to be enrolled in the program, Burns said, adding that states offer an optional eligibility pathway for individuals receiving long-term care services who make up to 300 percent of the SSI federal benefit rate.

“Beyond that, many people with disabilities are eligible for Medicaid through regular Medicaid eligibility pathways, such as the ACA expansion, and coverage for those groups would be at risk under a proposal that reduces Medicaid funding,” Burns said.

Another option highlighted by KFF analysis is a “buy-in” option that allows working individuals with disabilities to pay a premium for coverage. Eric Buehlmann, deputy executive director for public policy at the National Disability Rights Network, said this option is “hugely important for people to be able to maintain employment” because “it allows them to have those services and supports to then go to their job and be able to leave their house.”

But under Medicaid cuts, Buehlmann said states may retreat “back to what the program was at its core” and get rid of these options.